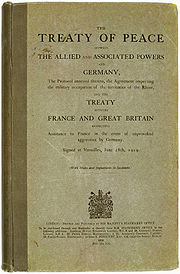

Treaty of Versailles - Peace in Humanity

The English Version

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of World War I were dealt with in separate treaties. Although the armistice signed on 11 November 1918 ended the actual fighting, it took six months of negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference to conclude the peace treaty.

Of the many provisions in the treaty, one of the most important and controversial required Germany to accept sole responsibility for causing the war and, under the terms of articles 231-248 (later known as the War Guilt clauses), to disarm, make substantial territorial concessions and pay reparations to certain countries that had formed the Entente powers. The total cost of these reparations was assessed at 132 billion marks ($31.5 billion) in 1921. The Treaty was undermined by subsequent events starting as early as 1932 and was widely flouted by the mid-1930s.

The result of these competing and sometimes conflicting goals among the victors was compromise that left none contented: Germany was not pacified, conciliated nor permanently weakened. This would prove to be a factor leading to later conflicts, notably and directly the Second World War.

Of the many provisions in the treaty, one of the most important and controversial required Germany to accept sole responsibility for causing the war and, under the terms of articles 231-248 (later known as the War Guilt clauses), to disarm, make substantial territorial concessions and pay reparations to certain countries that had formed the Entente powers. The total cost of these reparations was assessed at 132 billion marks ($31.5 billion) in 1921. The Treaty was undermined by subsequent events starting as early as 1932 and was widely flouted by the mid-1930s.

The result of these competing and sometimes conflicting goals among the victors was compromise that left none contented: Germany was not pacified, conciliated nor permanently weakened. This would prove to be a factor leading to later conflicts, notably and directly the Second World War.

France's aims

While both American and British leaders wanted to come to a fair and reasonable deal, France's interests were much more aggressive and demanding as many of the battles had been fought on French soil. Although they had agreed after the treaty was signed many world leaders agreed that some of France's demands were far too harsh and unsympathetic. France had lost some 1.5 million military personnel and an estimated 400,000 civilians to the war. (See World War I casualties) To appease the French public, Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau wanted to impose policies meant to cripple Germany militarily, politically, and economically, so as never to be able to invade France again. Clemenceau also particularly wished to regain the rich and industrial land of Alsace-Lorraine, which had been stripped from France by Germany in the 1871 War. Clemenceau wanted the Rhineland to be separated from Germany as it was a key area of industry.

Britain's aims

Prime Minister David Lloyd George supported reparations but to a lesser extent than the French. Lloyd George was aware that if the demands made by France were carried out, France could become the most powerful force on the continent, and a delicate balance could be unsettled. Lloyd George was also worried by Woodrow Wilson's proposal for "self-determination" and, like the French, wanted to preserve his own nation's empire. Like the French, Lloyd George supported secret treaties and naval blockades.

Prior to the war, Germany had been Britain's main competitor and its second largest trading partner, making the destruction of Germany at best a mixed blessing. Lloyd George managed to increase the overall reparations payment and Britain's share by demanding compensation for the huge number of widows, orphans, and men left unable to work through injuries due to the war.

Prior to the war, Germany had been Britain's main competitor and its second largest trading partner, making the destruction of Germany at best a mixed blessing. Lloyd George managed to increase the overall reparations payment and Britain's share by demanding compensation for the huge number of widows, orphans, and men left unable to work through injuries due to the war.

United States' aims

There had been strong non-interventionist sentiment before and after the United States entered the war in April 1917, and many Americans were eager to extricate themselves from European affairs as rapidly as possible. The United States took a more conciliatory view toward the issue of German reparations. American Leaders wanted to ensure the success of future trading opportunities and favourably collect on the European debt, and hoped to avoid future wars. Before the end of the war, President Woodrow Wilson, along with other American officials including Edward Mandell House, put forward his Fourteen Points which he presented in a speech at the Paris Peace Conference.